As a baby boomer with parents in their late 70s, their living situation is a growing concern for me. My folks are still ok driving, they maintain the yard and house, and they are physically active. But we all see a day coming when they will not be as self-sufficient and active as they are now.

As their likely caregiver, their location dictates where I spend a lot of my vacation time in the next few years. Happily for me, that’s Skidaway Island in Savannah, Georgia (pictured above. Thanks Mom and Dad!). The island has 10,000 residents, about as many as Cadillac. There is a good grocery store, library, health club, a restaurant, a couple of churches, and a pharmacy accessible by road as well as a walking/golf cart path, but doctors and other stores are off the island and require a car – there’s no public transportation. I’d like to see them stay in their house if that’s what they want, but clearly they will need some help as they become less mobile.

They may also find that their social opportunities diminish with their transportation options. Mom’s book club and bridge group are on the island but not walkable. Dad’s social circle is his golf group, which plays off the island. A criticism of the “aging in place” model – put some grab bars in the bathtub and you’re good to stay – is that, sure, you can stay in your house, but unless you can still drive, you can’t actually leave your house. In some residential situations, people who age in place may become more isolated than if they were in an institution. New York Times columnist Jane Brody wrote this column a few weeks ago about aging in place - from the perspective of a woman in her 70s. It's worth a read if you're interested in the topic.

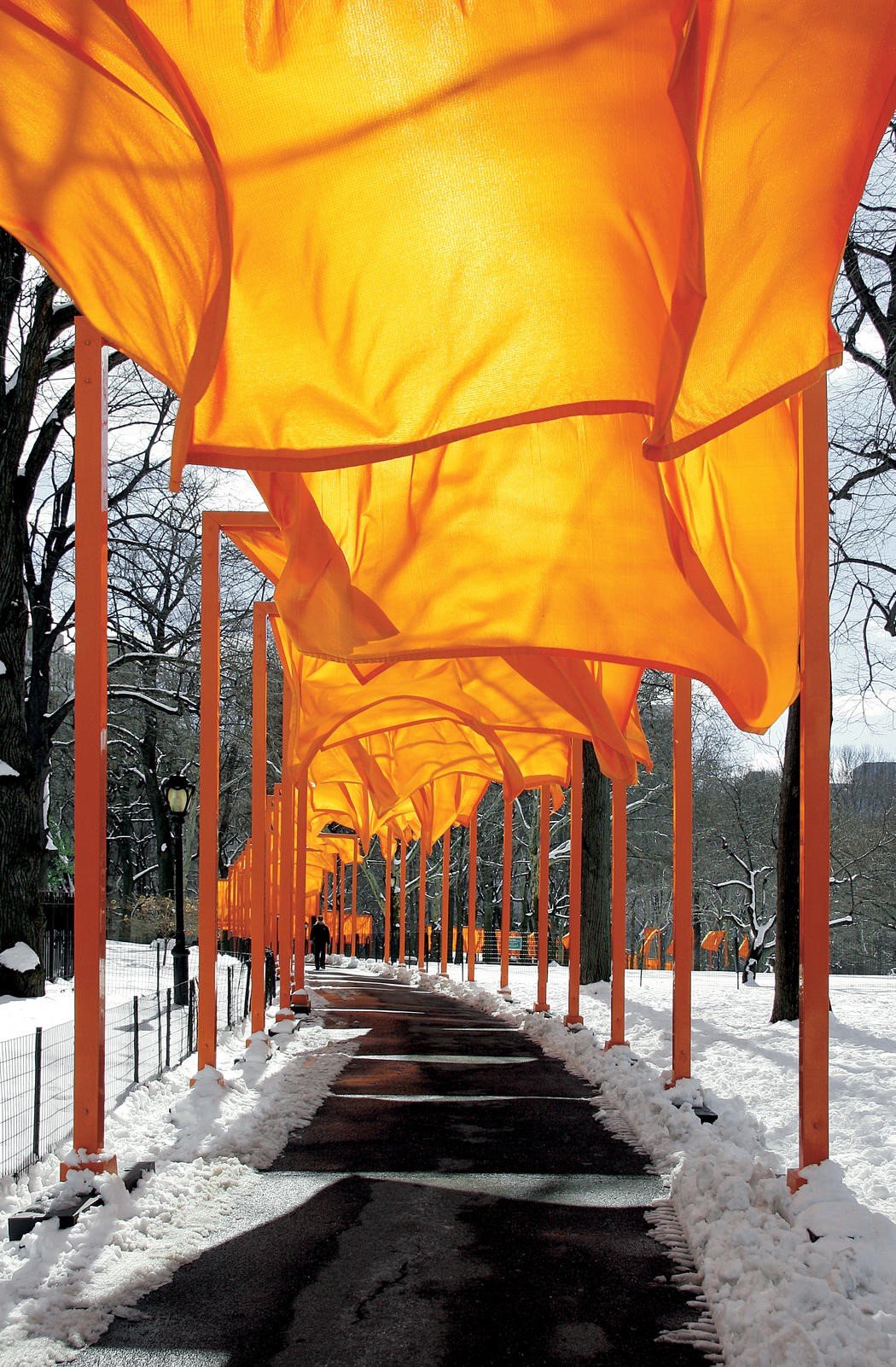

The World Health Organization has identified eight factors that contribute to age-friendly communities: community services and health care; transportation; housing; social participation opportunities; outdoor spaces; respect and social inclusion; opportunities for civic participation and work; and communications and information. The AARP has livability fact sheets for community planners that cite bicycling as a transportation option, dense, walkable neighborhoods, trees, and traffic calm as assets to make “great places for people of all ages.” Hmmmm, sound familiar? These have a lot in common with that list of placemaking characteristics I included in a previous post (see below). If we’re going to do placemaking, it should be for EVERYONE. Not just hipsters, not just artists, not just bloggers.

12 Steps to a Great Public Space

- Protection from traffic

- Protection from crime

- Protection from the elements

- A place to walk

- A place to stop and stand

- A place to sit

- Things to see

- Opportunities for conversations

- Opportunities for play

- Human-scale

- Opportunities to enjoy good weather

- Aesthetic quality

To which I would add:

Opportunities for active engagement and participation

Opportunities for quiet and reflection

Places to get food and drinks

Ideally, elders wouldn’t be segregated unless they wanted to be. A well-designed and executed community wouldn’t need special housing or amenities for the elderly and/or disabled, because health care, transportation, opportunities for civic participation, and outdoor spaces would be there for the hipsters, artists and bloggers already. Communities that are walkable with nearby services allow people who don’t drive to maintain all or most of their activities as they age. Walking creates all kinds of benefits – health, social, local economy, and environmental. Amenities for pedestrians usually translate pretty well to people on wheels – wheelchairs and walkers as well as bicycles and strollers.

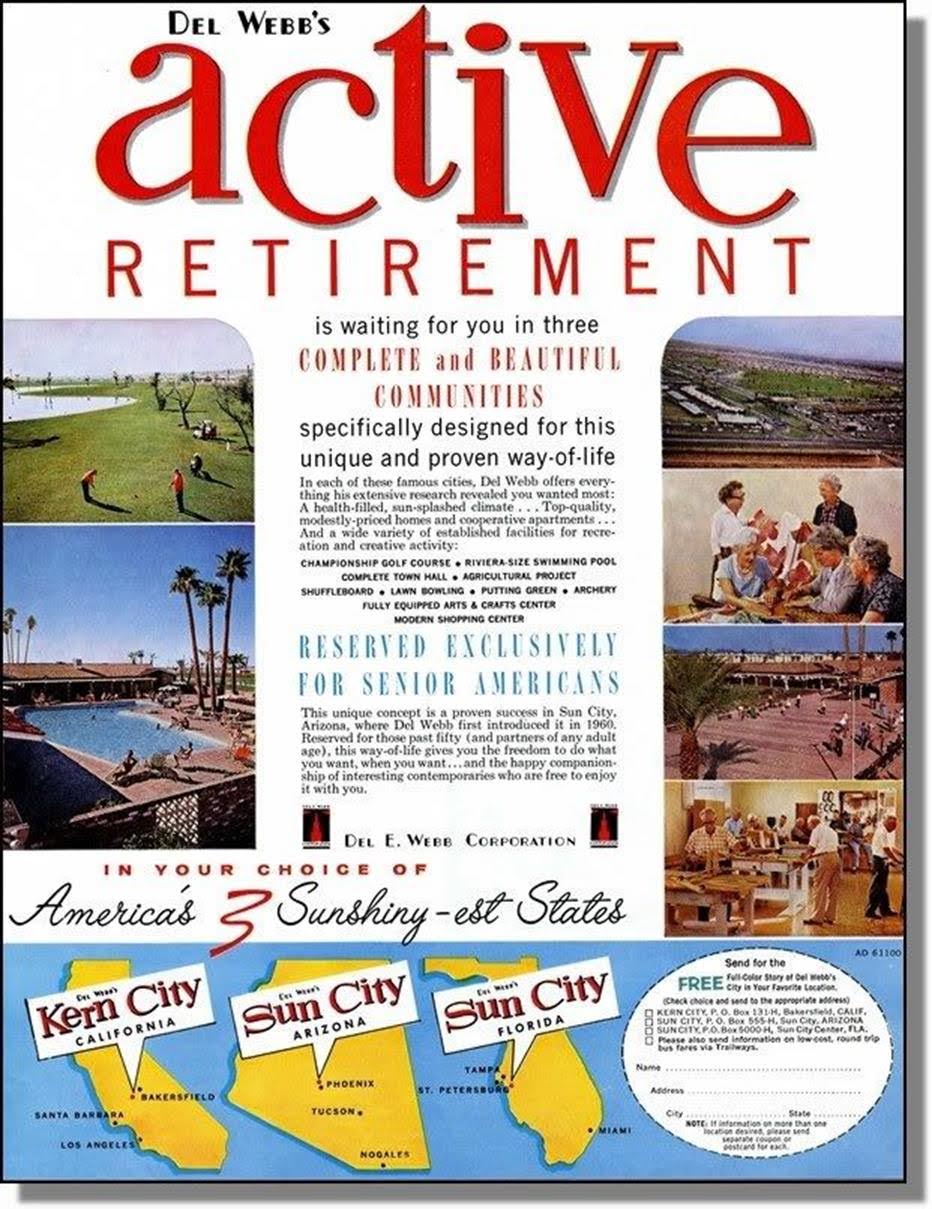

This ad is from 1962. Lawn bowling! Archery! Shuffleboard!

There is a range of housing options targeted to aging people. And the concept of placemaking, no surprise, is influencing developments for older adults.

Age-restricted communities were hatched in the 1960s – gigantic suburban-type developments for people over 50 with onsite activities like golf and shuffleboard (Sun City, in the ad above, was one of the first). Contemporary aging boomers are more interested in bike trails than shuffleboard, and many of us will be working until we drop, so more age-limited communities are being built near cities where residents can keep working, ride the trails, and have diverse opportunities for social and civic engagement, rather than be isolated in the middle of the desert.

Elders who don’t necessarily want to be segregated, but may be by circumstance, are influencing nursing home development too. Nursing homes are not really “places” in the sense that we use the term, but this article describes an alternative to traditional / institutional nursing homes that incorporates placemaking concepts. The Green House model described is based on 10-person units where private rooms are built around a living room where residents can socialize. Each unit has a kitchen, and residents and staff work together to plan meals and activities. Green Houses’ smaller scale facilitates interaction between residents which include mixed populations (not all elderly people)… all placemaking concepts that make these less institutional facilities and more desirable living communities. Other nursing homes are facilitating social interaction between elders and youth, from preschoolers to college students.

And then there are theme retirement communities. Born to be wild? Harley riders, feel confident there is a place for you and your people even as you age. Some college campuses, including University of Michigan, have affiliated retirement communities with classes available to residents.

Born to be wild in a retirement community for Harley owners. Are those golf clubs on the back of Fonda's bike??

As with anything else, it’s all about having options. My parents like their suburban setting and I’m happy to visit them there. If we can figure out their transportation off the island, aging in place may be a great option for them. My grandmother relocated from Royal Oak to an age-restricted independent living apartment in Florida to be near her five cousins, transitioning over time to assisted living. My favorite neighbor (who’s 86) wants to move into town where he can walk to meet his buddies for breakfast and to the bank to flirt with the tellers.

The AARP says that one in three Americans is over 50 years old, making us demanding boomers a pretty substantial force for retirement housing choices and associated amenities that meet our needs and innermost desires. Oh the places we’ll go!

Congratulations!

Today is your day.

You're off to Great Places!

You're off and away!

― Dr. Seuss, Oh, The Places You'll Go!

Bonus material!

The Times published several articles a while back describing issues that affect elders even in walkable, densely-developed cities: where can older people congregate within a walkable distance for them, socialize, but not be isolated with only other older people? Here is the first article in the series about police evicting loitering 80-year-olds from a Flushing, NY McDonald’s, followed by responses to it, then this editorial. This last article describes McDonald’s as a Naturally Occurring Retirement Community – the places that people gather because of convenience and amenities.

And the last word on the subject of aging boomers…

As always, thanks for reading. I welcome your comments, ideas, suggestions, and innermost desires for your own retirement situation, either through the comments section here, by email at ordinaryvirtues@gmail.com, or at www.linkedin.com/susanwenzlick.

#ordinaryvirtues